The Metric Mindset

Efforts to leverage sustainability rankings to drive investment are well meaning, but may not be producing the desired effects

If you’ve ever had a quota carrying job, you understand the importance of metrics and the impact they have on the decisions you make. Whether it be hitting an annual sales number, optimizing an AI algorithm for certain performance levels, or designing a website to maximize visits from your target audience, metrics guide daily activities and decision making.

At the international level, gross domestic product (GDP) is a critical metric that provides a snapshot of a country’s total goods and services sold over a given period of time. If a country is meeting its stated GDP growth goals, things are going well. If it misses the mark or even delays the release of those figures, it can cause trouble.

Although its economic data has long been questioned for its accuracy, China may be one of the world's best examples of a country whose GDP figures can move markets and cause repercussions throughout the global economy.

To believe or not believe

China GDP skeptics may have felt emboldened when, in 2007, Li Keqiang, then head of China’s Liaoning province, remarked to then US Ambassador to China Clark Randt that China's GDP figures were "man-made." In lieu of traditional GDP numbers, Li said he preferred a set of economic indicators that included data from freight shipping, electricity consumption, and loan rates. Dubbed the "Keqiang Index," Li felt that these core data points more accurately reflected the state of China's economy and its growth trajectory.

GDP is not an energy-specific metric, but I find the comments attributed to Li to be a helpful reminder that, just because GDP has been the traditional marker of a country's economic success, doesn't mean it is the only way to evaluate performance. In fact, as economist Joseph Stiglitz argues, we should create new tools and metrics to measure what matters and ensure that countries and companies are aiming at the right targets.

Greening the scorecard

Sustainable investing exemplifies Stiglitz’s idea that new performance metrics can and should be created and used to drive new ways to prioritize investments and gauge success.

While sustainable investing is a relatively broad and evolving term, its aims are clear - invest in "green" companies that are making honest attempts to reduce their environmental impact.

While laudable in its goals, a recent research paper from economists Kelly Shue and Samuel Hartzmark casts some doubt on the current metrics and strategies around sustainable investing.

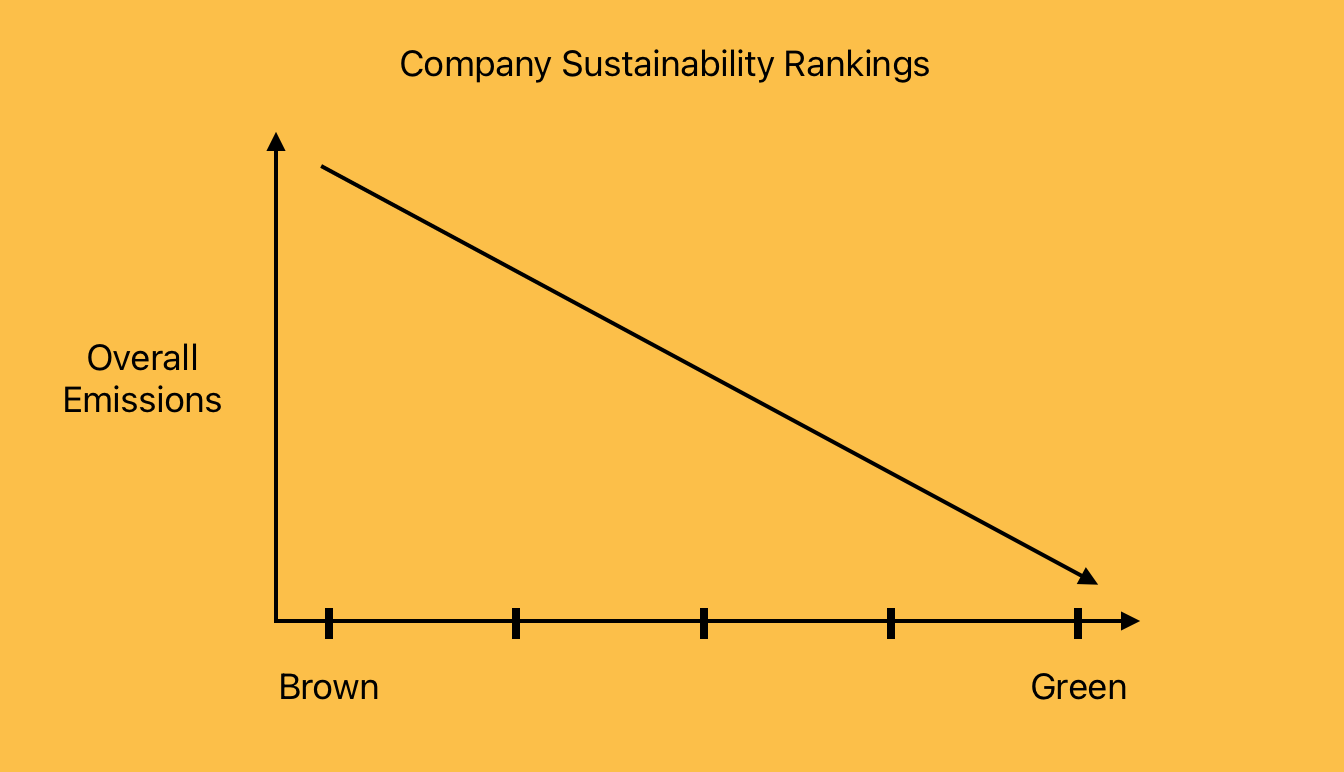

Shue and Hartzmark begin their paper by placing companies on an emissions spectrum that ranges from brown to green. "Brown" companies are those that have a negative environmental impact due to excessive emissions. "Green" companies, as you might imagine, fall on the opposite side of the spectrum and have relatively low emissions and environmental impact.

Current strategies around sustainable investing that look at percentage reductions in overall emissions would generally prioritize investments in companies that fall in or near the "green" category.

On paper, this sounds logical and effective.

Reward those companies that have a neutral or positive environmental impact by granting them easier access to capital. Punish the polluting "brown" firms that pump greenhouse gases into the atmosphere at an alarming rate.

Just because GDP has been the traditional marker of a country's economic success, doesn't mean it is the only way to evaluate performance.

The issue is that many "green" companies produce very low emissions to begin with.

Consider companies that operate in the insurance, software, or financial services spaces. They can be considered green because they aren't producing physical goods and, aside from the emissions produced by running buildings, taking flights, and buying office products, they aren't doing much to hurt the environment.

"Brown" firms, however, are the big emitters involved in sectors such as mining, transportation, and heavy industry. These companies are enormously important to the functioning of the global economy, but, due to nature of the job, they emit tremendous amounts of carbon. As Shue and Hartzmark find, firms following sustainable investing strategies will avoid investing in these “brown” companies, thereby raising the cost of capital and potentially putting them in financial distress.

Quoting directly from the paper:

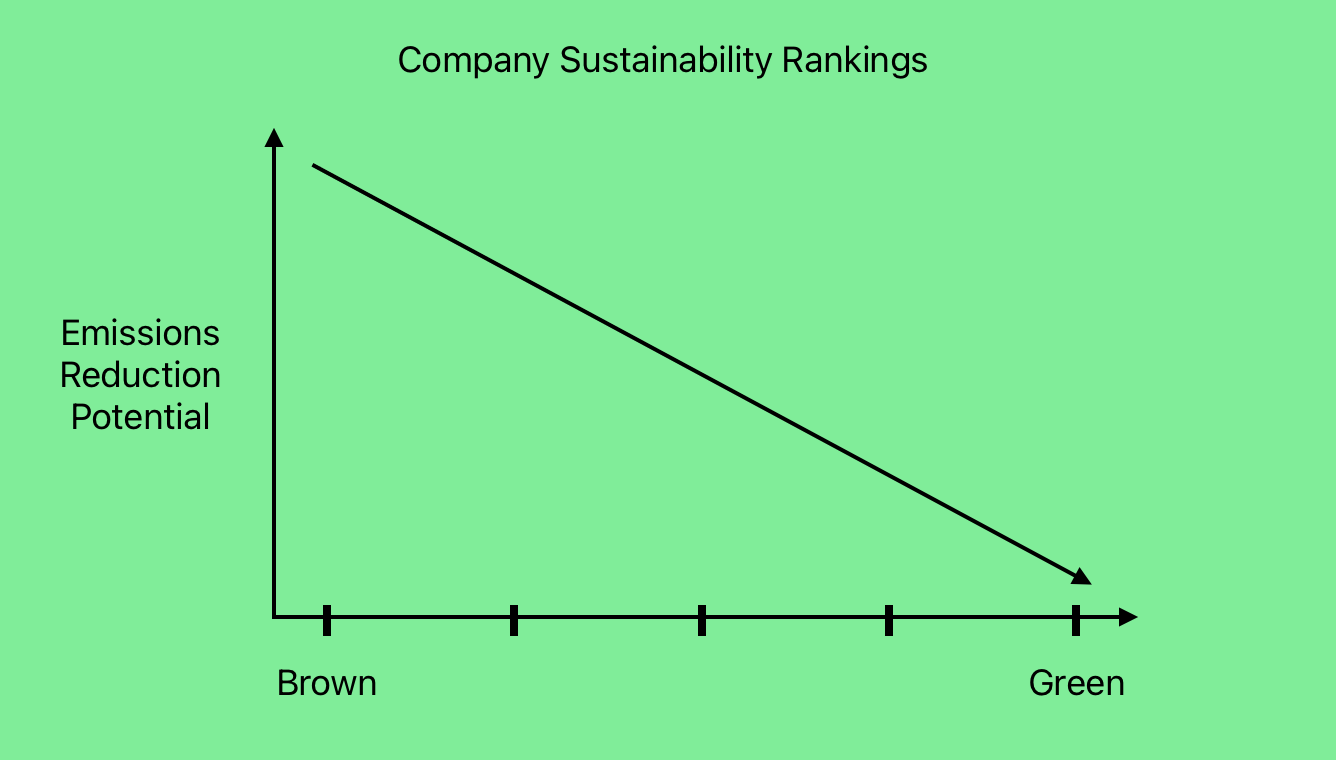

The most common sustainable investing strategy dictates that investors should invest in Travelers [an investment company] and avoid Martin Marietta Materials [a mining company]. With that said, if the money flows toward Travelers allowing further investments in green projects at subsidized rates, where would it go? If Travelers were to cut emissions by 100%, it would be equivalent to Martin Marietta cutting its emissions by a mere 0.1%.

Jumping to the conclusion:

We show empirically that a reduction in financing costs for firms that are already green leads to small improvements in impact at best. Increasing financing costs for brown firms leads to large negative changes in firm impact. We further show that the dominant sustainable investing strategy provides very weak incentives for brown firms to become less brown.

Aligning intentions and outcomes

In other words, while it may seem logical to punish those companies who are the largest emitters, by doing so, investors are restricting “brown” companies’ access to capital, placing them in financial distress, and discouraging them from making the necessary investments to partially or fully decarbonize their operations.

As Shue and Hartzmark conclude, sustainable investment strategies “primarily reward green firms for economically trivial reductions in their already low levels of emissions.” If sustainable investing is meant to have the greatest possible impact on reducing emissions, then it needs to be reformulated.

Key Takeaways

Consume less, emit less

As mentioned in previous posts, most current solutions to global carbon problems involve exchanging one technology for another in order to reduce emissions. It goes without saying that if we travel less, buy less, and consume less, we tackle carbon problems from another, potentially more impactful angle. This thought leads into the next point that countries and companies should…

Look beyond GDP

Whether it be well-known metrics such as GDP or more creative indicators like the “Keqiang Index,” there are innumerable combinations of quantifiable goals that can be set for a country or firm. If the high-level goals are money and profit, countries, companies, and people will pursue those aims, regardless of the costs. Given the incredibly urgent need to decarbonize every element of human life, now is the time to reevaluate traditional international macroeconomic metrics such as GDP and find goals that prioritize both human and environmental health and well being.

Course corrections

Even the most carefully planned goals need to be revisited from time to time. Just as a ship’s pilot needs to continually check to ensure he’s on course, countries and companies must look at their own metrics from time to time and confirm that their chosen metrics are driving the right behavior and choices. As Shue and Hartzmark demonstrated in their recent paper, sustainable investing has well meaning goals, but may be missing the mark when it comes to driving the maximum reduction in emissions.